Winner, Crow Writing Contest, 2021

By Sofia Garduño, University of Arizona

Sofia Garduño, originally from Tijuana, Mexico, is a first generation college student studying at the University of Arizona. She is currently majoring in Physiology & Medical Sciences and plans to attend medical school. When she isn’t contemplating the mysteries of the universe, she enjoys traveling, eating good foods, and baking cookies with her dog, Moose. “The dead are not gone, but rather flowers that have returned to the earth, buried, waiting.”

Introduction

The reverence for both life and death have been important cultural aspects of both Mesoamerican and South American communities since pre-Columbian (Nutini). Indigenous cultures sprung up throughout the continent, however, beginning in the 1500’s, the colonization of Latin America by the predominantly Catholic empires of Europe spread Catholicism through their invasion of Central and South America. As a result, the practice of pagan traditions began to be intertwined with Catholicism in order to be preserved and protected from the brutality of colonization. As a by-product of the European influence in the Americas, a diffusion of culture took place.

This research project will explore how colonization created variations in celebrations of All Souls Day celebrations by examining the traditions of Mexico, Brazil, and El Salvador. The festivities of Mexico’s Día de Los Muertos, El Salvador’s El Día de Los Difuntos & the country’s lesser known celebration of La Calabiuza, and Brazil’s Día de Finados will be the in focus for this paper; their customs, origins, and modern-day impact will be examined topics. In order to conduct more organized research, I will be drawing comparisons from the customs of the largest/most prevalent indigenous population — as there are many communities with their own customs. By analyzing the differences and similarities in the traditions of the celebrations of life and death in Mexico, Brazil, and El Salvador, I will draw links between each country’s customs and how they were distorted by each nation’s colonial legacies.

Catholicism’s Lingering Practices: All Saints Day/All Souls Day

The observations in focus of this research essay are the Catholic holidays of All Saints Day and All Souls Day. The origin of these holidays, because they are two separate holidays, stems from Catholicism brought over by Europeans hoping to expand their religion along with their empires. All Saints Day, observed on November 1st, began as a means to honor the vast amount of saints, particularly martyred ones; as most saints has a specific feast day, it grew impossible for each martyred saint to have their own feast day, so a universal celebration became the most practical option (Saunders). In a similar sense, All Souls Day, observed on November 2nd, occurred as a result of churches holding separate and disorganized masses in remembrance for the departed souls of those who attended their local churches (Saunders). Eventually, the church adopted November 2nd as a universal Feast of All Souls (Saunders).

The colonization of the Americas was one of the most brutal and dehumanizing periods of the world’s history. The indigenous people of the Americas were forced to adapt to European customs as a means of survival. The rituals that were practiced to honor the dead by the native people merged into Catholicism as camouflage to continue to practice their religions and worship their gods. As a by-product, “After Christmas and Holy Week (Easter), All Saints Day-All Souls Day is the most important celebration in the annual cycle of folk Catholicism in Mesoamerica” (Nutini). In turn, each Latin American country now holds their own variation of their celebration of life and death, each celebrating their ancestors with the influence of their regional indigenous cultures, as influenced by their unique colonial histories.

México — Día de Los Muertos

Prior to the colonization of present-day Mexico, the indigenous cultures that were present in Mesoamerica were polytheistic, loosely-allied city-states. The predominant indigenous populations that resided in Mexico at the time of the Spanish conquest were the Olmecs, the Aztecs, the Zapotec, and the Maya (Indigenous Civilizations In Mexico). While each of these cultures possess unique and individual traits, the general attitude towards death is one in which “the country and the city come together, the little community becomes the cosmological center of existence, and individuals and families are renewed by remembering their roots and paying homage to those who have departed” (Nutini).

Prior to the introduction of Catholicism to Mesoamerica, the celebration of life and death practiced by Mesoamericans took place following the agricultural calendar, specifically the cycle of maize cultivation (around July-August) and lasted around a month (Alimentarium). According to pre-Hispanic customs, the first festival day honored deceased children and was called Miccaihuitontli and the second festival day (that took place 20 days later) honored deceased adults and was called Hueymiccalhuitl (Volant). Today, Día de Los Muertos similarly takes part in two distinct days: November 1st for deceased children (Día de los Inocentes) and November 2nd for deceased adults (Día de los Muertos) (Richman-Abdou et al.). In Mesoamerican culture, death was viewed as a necessity for life, and was viewed as more of a journey through another world once a persons’ time in this one was completed. This season was regarded as a joyous affair, one in which sadness and grief for the departed was unwelcome due to “tears of grief … [making] the return journey [through the underworld] slippery and dangerous for the deceased’’ (Alimentarium). The deity of which this festivity was dedicated to was Mictēcacihuātl, the goddess of the underworld. Upon the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century and the French in the 19th century, the forceful introduction of Catholicism saw the month-long celebration of death condensed into a 2-3 day festivity. What we now know as Día de Los Muertos, continues to draw from its pre-Hispanic roots through its traditions and symbolism (fig. 2).

While inaccurate, Día de Los Muertos has oftentimes been referred to as the “Mexican Halloween,” and while the excitement and festivity that surrounds the 3 day period may appear similar, nothing could be farther from the truth. While Halloween and Día de Los Muertos may seem connected to an outsider, there is a vast difference: All Hallows Eve (aka Halloween) was a way to ward off evil spirits, while Día de Los Muertos was a means to bring spirits of loved ones back home for a few nights and celebrate the life of ones who have passed on.

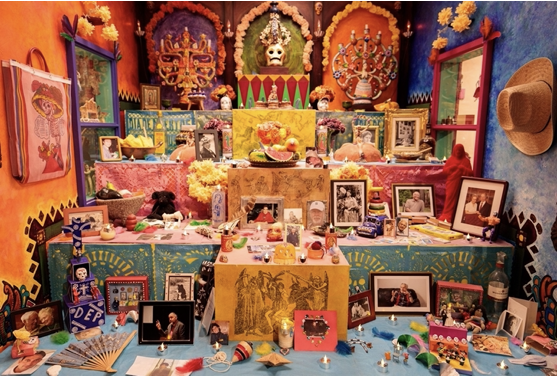

As the holiday of Día de Los Muertos may now be leaning towards a more commercialized version of what it once was, it continues to echo pre-Columbian practices. It’s likely that when one creates a mental image of Día de Los Muertos, they think of the colorful papel picado, the cempasuchil, and the ornate calaveras that decorate ofrenda — altars dedicated to departed loved ones that are meticulously decorated and cleaned prior to the festivities on November 1st and 2nd (fig. 3). This custom remains from the days prior to Spanish colonization in which indigenous people “provided food, water and tools to aid the deceased in this difficult journey” (Day of the Dead). Today, one doesn’t necessarily leave a knife or shovel for a deceased soul to take into the underworld, but they do place their favorite food and drinks instead. Another popular symbol of Día de los Muertos is La Calavera Catrina — originally a caricature of how Latinos adopted European customs (her dress is reminiscent of European-style clothing). Affectionately called La Catrina by many, has come to represent not only Día de Los Muertos, with her opulent dress and makeup and iconic hat, but the goddess Mictēcacihuātl also.

El Salvador — El Día de Los Difuntos & La Calabiuza

The influence of colonial rule in El Salvador mirrors Mexico in many ways. The involuntary conversion to Catholicism at the hands of the Spanish colonization nearly eradicated the indigenous population of the region. The primary native population that lived in the region that would be known as El Salvador was the Pipils, a migrant Nahua speaking group from central Mexico (Fowler). The Pipils people even shared many of the same deities as the other Mesoamerican cultures that resided in Mexico, one of them being Mictēcacihuātl, the goddess of the underworld (Fowler). Worshipping common deities most likely contributes to shared cultural similarities as well. A distinction between El Salvador’s celebration of life and death is that it has two distinct holidays — El Día de Los Difuntos & La Calabiuza.

El Salvador’s El Día de Los Difuntos shares many similarities with Mexico’s Día de Los Muertos. Both versions feature decorated ofrendas, adorned with flowers and candles, topped with the favorite foods of the departed. While El Día de Los Difuntos has the same joyous atmosphere as Día de Los Muertos, it is considered to be a much more reserved celebration in comparison; there are no grand parades or processions like in Mexico. Instead, El Día de Los Difuntos is a time used by many for reflection and quiet gathering with family. In contrast to the quiet, cheerful festivities of El Día de Los Difuntos — El Salvador also celebrates La Calabiuza. This carnival-like celebration is filled with revelry and chaos, making way for the spirits of the dead to arrive for El Día de Los Difuntos the next day. The festivity, a pre-Hispanic tradition, takes place on November 1st, the night before El Día de Los Difuntos, on November 2nd. There is no accurate record of where the tradition of La Calabiuza stems from religiously (its indigenous roots), but the general consensus is that the celebration is meant to reject the lore of the Spanish and the Americanized Halloween, and instead to embrace the regional lore and legends of Central America. Today, La Calabiuza also serves as a night of reprieve; El Salvador has the 2nd highest murder rate in the world, but for one night “it turns young people away from violence” (Agence France-Presse). The customs signature of La Calabiuza are children and teenagers dressed up as different Central American legends (La Llorona, el Cadejo, Cipitío, etc.) and going door-to-door begging for sweets, specifically ayote — pumpkin cooked in honey or brown sugar (fig. 4 & 5). Processions take place throughout the streets of hand-drawn carts called las carretas chillonas that travel from the town cemetery to the town center, surrounded by revelers painted in white, black, and red to represent the dead (fig 6) (Rivera).

Despite El Salvador’s indigenous cultural similarities to Mexico, the impact of colonialism fractured Central America and South America far more than Mexico. The turmoil left in Central America specifically has seen an epidemic of violence — primarily gang violence, civil wars, and trafficking. These valuable cultural traditions almost came to an end during El Salvador’s civil war (from 1980 to 1992). The civil war occurred between the government and communist grassroot organizations. The insurgent force that gathered against the government was primarily composed of poor indigenous and rural Salvadorians still feeling the effects of Spain’s encomienda systems, forced slave labor, that subjected them to generational poverty. This oppositional force was met with brutality and violence that violated all humanitarian accords, one of these tactics being “death squads” that were ordered to kill “anyone who looked indigenous” (Minority Rights Group). As a consequence of this conflict there was further detrimental loss to indigenous communities with already depleting populations. This cultural loss emphasized to many the importance of reviving many regional traditions, such as La Calabiuza.

Brazil — Día de Finados

Brazil, unlike Mexico or El Salvador, had no central indigenous empire like the Aztecs or the Pipils people, but there were hundreds of native tribes with a total of approximately 4 million people between them all (Minority Rights Group). When Portugal arrived on the shores of South American in the 1500’s, the intentions of colonization were never to create an extension of their empire, but rather, “ … a junior partner in a commercial system organized around the spice fleets.” (Lang, pg 6). Initially, the interactions between the Portuguese and the indigenous population were polite. Nonetheless, the patterns of violence, disease, and exploitation prevailed in Portugal’s colony like all others: the Portuguese’s desire to exploit sugar and brazilwood, a prized material at this time in Europe for the distinctive color of its wood and a red dye it produced, led to conflict. In turn, a cycle of brutality would deplete the almost “2,000 distinct tribes and nations’’ of pre-colonial Brazil, to around 300 as of today (Minority Rights Group). This drastic decline in the indigenous population, which the Portuguese were using for non-imported labor previously, generated the need for additional (free) labor: African slaves. The sheer quantity of enslaved Africans that the Portuguese would import would lead to Brazil having “… more slaves than any society in the Americas …” (Lang, pg 193).

This introduction of African slaves to South America carried with it a myriad of religions, languages, and traditions from all over Africa to Brazil. While indigenous people, Europeans, and African slaves have blended all over Latin America to create extraordinary mixes of cultures and customs, the product of Portuguese colonization in Brazil has created a mosaic like no other. This elaborate mixture, created from a multitude of indigenous Brazilian cultures, imported African practices, and European influence, produced a unique holiday that echoes features from each global imprint it carries.

It is said that Día de Finados represents the emotion of saudade, which is said to be “ … a feeling and only exists in Portuguese … caused by distance from someone or something you hold dear” (Kessler). This day is recognized as a national holiday and is observed on November 2nd, like many Latin American countries who practice their own variation. The origin of Día de Finados in Brazil derives from All Souls Day, a day to commemorate and pray for souls who have passed on, brought to Latin America through European colonization carrying Catholicism overseas. One would imagine that Brazilians would observe Día de Finados like they do Carnival, an annual festivity that takes place for a few days before Lent to fit some revelry in before a season of fasting and reflection. However, in Brazil, Día de Finados is a solemn, quiet day of contemplation. Dissimilarly from the festivities like Día de Los Muertos or La Calabiuza, there are no raucous crowds or explosive displays of colorful decorations. Instead, many spend the day attending mass, eating with their family, and visiting cemeteries to clean graves and leave flowers for loved ones (fig 7, 8, & 9). A popular tradition on Día de Finados is for family members of the departed to abstain from meat and or alcohol for November 2nd or longer; the act of giving up these simple pleasures is done out of respect for the dead.

A religious sect that deserves mention in the observance of Día de Finados is the religious practice of Candomblé. This religion, brought over by African slaves who mixed their customs with Brazilian natives and their Portuguese captors, “combines elements of African and indigenous religion with aspects of Catholicism” (Rudy). Followers of this denomination pray to orixás, sub-deities that mimic the function of Catholic saints as they pertain to specific aspects of life and the world. In those who practice Candomblé, during Día de Finados the orixá, Omolú, is prayed to as he is considered the orixá that guides souls through life and death; he is also considered the owner of cemeteries and is therefore honored on this day.

Conclusion

The touch of colonization is still felt profoundly throughout Latin America, not solely in the traditions and holidays that are observed, but in the patchwork of people that was produced as well. The festivities of Mexico’s Día de Los Muertos, El Salvador’s El Día de Los Difuntos & La Calabiuza, and Brazil’s Día de Finados demonstrate the withstanding grip of Catholicism and the ability to marry European customs to indigenous practices. Parallels that are worthy of note are the differences in which the countries highlighted in this research essay regard celebrations of death and life. Practices such as what types of flowers, food, or drink people leave on the graves of their loved ones are consistent throughout all of Latin America, and primarily only vary due to regional availability or preference. On the other hand, the attitude that is taken to honoring the dead varies across all celebrations that have been discussed. In Mexico, Día de Los Muertos possesses a much more exuberant and colorful approach to commemorating departed loved ones, as well as retaining visibly recognizable indigenous roots that can directly be traced back to the Aztec empire and surrounding indigenous tribes. In contrast, Brazil’s Día de Finado takes a much more mournful approach to remembering the souls of the departed, without jubilation or vibrant parades; the ties of Catholicism reflect strongly in their observance of All Souls Day. El Salvador’s El Día de Los Difuntos seems to meet the previous two holidays in the middle: it is neither as carnivalesque as Día de Los Muertos nor as pensive Día de Finado. La Calabiuza, a uniquely Salvadoran tradition, seems to simultaneously exist within the realm of being a celebration of life and death and something else entirely; as a means to turn away from violence, and instead to turn to myth. Whatever the customs that these celebrations follow, they are all products of indigenous practices conformed to imposed-upon Catholicism as a means of survival. The people who transformed European beliefs into their own design did so in response to lives filled with death at the hands of oppressors who attempted to exterminate their faith.

Bibliography

Agence France-Presse. (2013, Novembre 04). In El Salvador, citizens Reject Halloween and celebrate a unique day of the dead -. Retrieved March 04, 2021, from https://ticotimes.net/2013/11/04/in-el-salvador-citizens-reject-halloween-and-celebrate-a- unique-day-of-the-dead

Agence France-Presse. “A Girl in a White Dress with Large Angel Wings and White Face Paint.” La Muerte Espanta y Divierte En El Desfile Salvadoreño De La Calabiuza, Yahoo! Noticias, 2017, AQAAALLmMPdvtAnYZzyEPjRLQ206kVVkYe5NuC3gVbhNQURi1GzRlO16M8E7al7UB7IEdIJZfzYfTpTbUKXVw92DoiEkIfNywwKkIeGpVybl9aLTebWTsKy9ZdIA AAJLhdJY.

Agence France-Presse. “a Teenager Dressed up in a White Dress and Veil, Holding a Baby Doll, Painted as a Skeleton.” The Tico Times, 2013, ticotimes.net/2013/11/04/in-el-salvador-citizens-reject-halloween-and-celebrate-a-unique-day-of-the-dead.

Alimentarium, Ressources. “The Day of the Dead, a Bridge between Two Worlds.” Alimentarium, Alimentarium, 6 Jan. 2017, www.alimentarium.org/en/knowledge/day-dead-bridge-between-two-worlds.

Barrientos, Osvaldo. “A Woman in a Traditional Dress, Half Her Face Painted as a Calavera, Carries a Basket of Marigolds.” How Oaxacans Are Still Celebrating Día De Los Muertos This Year, Allegra Zagami, heremag-prod-app-deps-s3heremagassets-bfie27mzpk03.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/ uploads/2020/10/27152504/OsvaldoBarrientos-DiadeMuertos21.jpg.

Beatty, Andrew. “Skulls to the Living, Bread to the Dead: The Day of the Dead in Mexico and beyond – By Stanley Brandes.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, vol. 15, no. 1, Mar. 2009, pp. 209–211. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2008.01537_34.x.

Bond, Kathy. “All Souls Day in a Small Town of Paraíba, Brazil.” Maryknoll Lay Missioners, 2 Dec. 2019, mklm.org/brazil/dia-de-finados-paraiba/.

“Brazil: World Directory of Minorities & Indigenous Peoples.” Minority Rights Group, 17 Nov. 2020, minorityrights.org/country/brazil/.

Chiang, Joshua Y. “An Elaborate Altar in the Harvard Peabody Museum.” Harvard Affiliates Munch on ‘Bread of the Dead’ at Peabody Museum Día De Los Muertos Party, 2018, www.thecrimson.com/article/2018/11/2/dia-de-los-muertos-celebration/.

Cipriani R. (2019) Diffused Religion in Latin America. In: Gooren H. (eds) Encyclopedia of Latin American Religions. Religions of the World. Springer, Cham. https://doi-org.ezproxy1.library.arizona.edu/10.1007/978-3-319-27078-4_385

Cunningham, Lawrence , Marty, Martin E. , Frassetto, Michael , Pelikan, Jaroslav Jan , Oakley, Francis Christopher , Knowles, Michael David and McKenzie, John L. “Roman Catholicism”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 11 Nov. 2020, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Roman-Catholicism. Accessed 5 February 2021.

Fernandes, Thamyris. “A Cemetery Decorated with Flowers and Candles in Brazil.” Segredos Do Mundo, 2018, segredosdomundo.r7.com/dia-de-finados-o-que-significa-e-porque-e-celebrado-em-2-de- novembro/.

Fowler, Bill. “The Pipils of El Salvador.” Teaching Central America, www.teachingcentralamerica.org/pipils-el-salvador.

Garcia, Gustavo. “People in Traditional Aztec Dress Take Part in a Dia De Los Muertos Ceremony.” Scenes from Día De Los Muertos, Dominic Mercier, fleisher.org/scenes-from-dia-de-los-muertos/.

Galdamez, Eddie. “All Souls Day El Salvador. Remembering Those Who Passed Away.” El Salvador INFO, 11 Feb. 2021, elsalvadorinfo.net/all-souls-day-el-salvador/.

History.com Editors. “Day of the Dead (Día De Los Muertos).” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 30 Oct. 2018, www.history.com/topics/halloween/day-of-the-dead.

“Indigenous Peoples.” Minority Rights Group, 23 Nov. 2020, minorityrights.org/minorities/indigenous-peoples-2/.

“Indigenous Civilizations In Mexico.” Don Quijote: Spanish Language Learning, Ideal Education Group S.L., 1989, www.donquijote.org/mexican-culture/history/mexican-indigenous-civilizations/.

Kessler Writer , Sarah. “A Guide to Dia De Finados, Brazil’s Day of the Dead.” Cake Blog, 13 Jan. 2021, www.joincake.com/blog/finados/.

Kohn, Margaret and Kavita Reddy, “Colonialism”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2017/entries/colonialism/>.

Lang, James. Portuguese Brazil: The King’s Plantation. Academic Press, 1979.

Nutini, Hugo G. “Pre-Hispanic Component of the Syncretic Cult of the Dead in Mesoamerica.” Ethnology, vol. 27, no. 1, 1988, pp. 57–78. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3773561. Accessed 4 Mar. 2021.

Peña, Alexander. “Salvadorian Teenage Boys, Painted as Skeletons, Face the Camera and Participate in a La Calabiuza Celebration.” Xinhua, 2019, spanish.xinhuanet.com/2019-11/03/c_138524433.htm.

Richman-Abdou, Kelly, et al. “Día De Los Muertos: How Mexico Celebrates Its Annual ‘Day of the Dead.’” My Modern Met, 12 Dec. 2019, mymodernmet.com/dia-de-los-muertos-day-of-the-dead/.

Rivera, Alexia Ávalos. “Festival De La Calabiuza: Mitología, Leyenda y Ayote En Miel.” Balajú. Revista De Cultura y Comunicación De La Universidad Veracruzana, 2015, balaju.uv.mx/index.php/balaju/article/view/1986/3648.

Rudy, Lisa Jo. “Explore the Brazilian Religion Candomblé.” Learn Religions, 5 Aug. 2019, www.learnreligions.com/candomble-4692500.

Velasquez, Geovani. “People Stand at Graves Decorated with Flowers, Candles, and Statues in a Cemetery in Brazil.” Brazil Photo Press, 2013, brazilphotopress.photoshelter.com/image/I0000eCmN4Keq400.

Volant, Eric. “Mexico: Dia De Los Muertos.” L’Encyclopédie Sur La Mort , UNESCO, 2012, agora.qc.ca/thematiques/mort/dossiers/mexique_dia_de_los_muertos.

Copyright © 2021 Sofia Garduño. Published with permission.